Les Estampes de D Maes / The Prints of D Maes

Extrait du catalogue d’une exposition qui a eu

lieu à Chamalières, France, décembre

1998 - janvier 1999

Les gravures de David Maes peuvent au premier abord sembler austères : aucun paysage, aucun décor ne vient distraire

le regard. C'est l'homme, le corps humain qui tout entier l'occupe. Cet intérêt

tenace associé avec le souci de la simplicité est parfois confondu avec

l'austérité. De façon générale, les personnages que David Maes grave ne sont

pas précisément identifiés, en particulier on ne connaîtra pas, sauf exception,

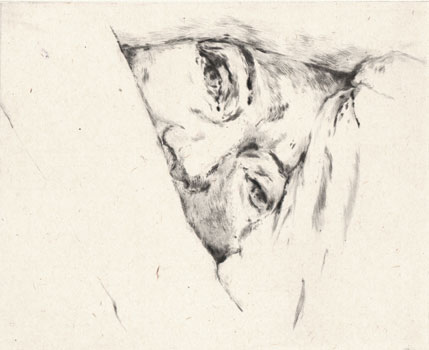

les traits de leur visage. (L'exception étant ce portrait d'une jeune femme,

dont le visage inscrit dans le triangle formé par son bras replié, est imprégné

d'érotisme discret. Le titre : Portrait,

se référant strictement au genre, préserve cependant l'anonymat.). La pointe

sèche, qu'il pratique de façon régulière en l'associant avec d'autres

techniques, dégage les silhouettes, ourle les rondeurs ou les creux des corps,

saisit les mouvements, jusqu'aux hésitations les plus imperceptibles. Il

dessine, il peint, il grave des hommes, des femmes, des enfants le plus souvent

nus. La nudité n'est pas chez lui un artifice mais le moyen le plus rapide

d'atteindre l'intimité de chacun. "Chaque corps dégage une énergie

différente" dit-il, et ce qui lui importe, c'est de saisir cette présence

charnelle.

Cette simplicité n'altère en rien le trouble que les images peuvent

causer. Dans Femme et enfants,

gravure qui possède son pendant en peinture, une scène de baignade presque

banale peut aussi être un moment de

tension et d'angoisse. Trois enfants barbotent dans l'eau ; à l'arrière, une

femme se penche vers eux, les bras écartés. S'agit-il d'un moment de détente

partagé entre une mère et ses enfants ? Ou bien, les bras largement ouverts

("comme pour mieux vous saisir, mes enfants"), la femme ne

cherche-t-elle pas à les capturer ? Elle incarne tour à tour la mère attentive

et une figure contemporaine de l'ogresse, à laquelle les enfants cherchent,

timidement, maladroitement, à échapper. L'ambiguïté de l'image tient dans

l'aller-retour entre ces deux visions, elle est de même nature que le flou

volontairement entretenu du jeu : "se faire peur pour de rire".

Les gravures de David Maes, sous leur apparence de simplicité, se

prêtent à de multiples interprétations, et révèlent parfois des aspects sombres

et graves de la nature humaine ; en revanche, elles ne reflètent jamais les

univers tourmentés et complaisamment morbides de certaines personnalités. Au

contraire, de ses estampes se dégage une sorte d'optimisme, de confiance dans

l'être humain. Homme marchant III,

figure récurrente dans son travail, est avant tout un homme qui se tient

debout. Juste un homme pourrait-on dire, mais un homme qui avance. Seul,

imperturbable, il impose sa présence. Ce que David Maes met en avant, c'est la

dignité de l'homme à travers un destin que l'on devine pesant. L'homme avance

et rien d'autre ne compte.

br>

Les thèmes autour desquels la pointe du graveur vient sans cesse

creuser rejoignent parfois une certaine forme de mysticisme. La voix, pointe sèche dont la

composition se rapproche de celle d'un diptyque, en est un exemple.

Dans la partie inférieure gauche, un homme, avance, le front buté, un peu penché

en avant. Seul le haut de son corps, est visible. A l'opposé, en haut à droite,

une forme est suspendue : une voix, un souffle ou un ange comme le suggère le

titre de la peinture L'Homme et l'angequi,

de quelques années antérieure, reprend la même composition. Cette figure

tutélaire, qui dans la gravure n'est pas si précisément nommée, manifeste que

malgré sa solitude l'homme n'est pas abandonné.

D'autres thèmes traditionnellement religieux sont parfois évoqués dans

les gravures de David Maes. En particulier, il s'est longtemps intéressé à la

crucifixion. Avec Trois études de corps,

il a abordé en 1993 le sujet d'une manière complètement originale, en le

confrontant avec un rituel qui lui tient particulièrement à coeur : la

tauromachie. Le titre, volontairement neutre, n'évoque pas à priori cet

univers. Pourtant, les attitudes des corps de chacune des trois gravures

peuvent être mises en parallèle avec celles, traditionnelles, du torero. Mais à

chaque fois, dans ce jeu de comparaisons se glisse la figure de la mort. Porté

en triomphe sur les épaules d'un de ses pairs, le torero n'est qu'un squelette

; le corps, auquel on a retiré la cape, se retrouve écartelé, crucifié ; enfin,

cambré pour planter ses invisibles piques, le corps du banderillo semble tendu,

comme un arc, par la souffrance. La composition générale renvoie encore à

l'univers de la tauromachie, puisque les trois gravures s'inscrivent dans le

demi cercle de l'arène.

Polysémiques, les gravures de David Maes se transforment sous notre

regard. Dans un travail plus récent, Daphné , David Maes a cherché à

rendre visibles les transformations d'une image. En se recommandant d'Ovide, il

tente de représenter les Métamorphoses.

Ainsi, sous nos yeux, Daphné se transforme en laurier, puis l'arbre de nouveau

se change en femme. Le cycle des métamorphoses trouve avec la technique de la

gravure un médium idéal puisque, on le sait, une des spécificités de cet art

est de pouvoir montrer les états, alors que la peinture, sauf à user de

l'artifice de la photographie, est condamnée à disparaître sous le nouveau coup

de pinceau. Ce n'est qu'à partir du dix-septième état que la figure de la femme

a vraiment trouvé son équilibre, et c'est à partir de cet état, que nous la

voyons évoluer. Accroupie, ses bras relevés fleurissent. La présentation des

états permet de montrer la transformation un peu comme le ferait un film pour

l'éclosion d'une fleur.

De fait, cette transformation semble très longue. Le temps s'étire. La

métamorphose devient palpable, presque consciente. En revanche, dans une autre

métamorphose, Daphné II, David Maes

annule ce processus. Il se contente alors de juxtaposer, dans un diptyque

vertical, deux instants. La métamorphose n'est plus qu'un choc. Un corps,

soumis à la pesanteur, tombe. (Pour une fois, ce corps n'est pas strictement

humain, mais possède, peut-être dans le poids que l'on mesure du regard,

quelque chose d'animal). Vers le haut, une forme végétale s'épanouit. Les

directions opposées renforcent encore la violence du choc, le caractère

irréversible de la métamorphose. La manière dont David Maes aborde le thème des

métamorphoses montre que loin de vouloir enfermer son œuvre dans un univers

statique, il cherche au contraire à explorer toutes les possibilités offertes.

Marie-Hélène Gatto

Conservateur, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Text from Catalogue for an exhibition in Chamalières, France, December 1998- January 1999

At first David Maes’ etchings may seem austere; neither landscape nor decor competes for our attention. Maes is concerned only with humanity, with the human body. This consuming interest, which is based on a commitment to simplicity, is sometimes mistaken for austerity. Maes’ people are not generally defined with precision. The features of their faces, in particular, are, with rare exceptions, left undelineated. (One exception is the portrait of a young woman whose face, bounded by the triangle of her folded arm, is imbued with discreet eroticism. Even here, however, anonymity is preserved by the generic title: Portrait.) The dry point needle, which he regularly uses in combination with other techniques, accentuates the silhouettes, outlines the curves and hollows of the body and captures its movements, even its least perceptible hesitations. Maes draws, paints, and etches men, women, and children, usually nude. For him, nudity is not an artifice, but the most direct route to human individuality. « Every human body emits a characteristic energy, » he says, and what matters most, he believes, is to seize hold of this sensual presence.

Despite its simplicity, Maes’ work has the capacity to disturb us.Woman and Children, an etching with a companion piece in oil, can be seen either as an almost banal bathing scene or as a vision of tension and anguish. Three children are splashing in the water; in the background, a woman is leaning towards them, arms outstretched. Is this a moment of relaxation shared by mother and children? Or, with arms outstretched (« All the better to hold you with, my children ») is the woman trying to capture them? One moment she seems to be an attentive mother, the next a contemporary ogress from whom the children are, timidly and awkwardly, trying to escape. The ambiguity of the image lies in the to-and-fro movement between these two ways of seeing.

Beneath their apparent simplicity, David Maes’ etchings are open to several interpretations and sometimes reveal dark and deep areas of human nature. However they never dwell on the tormented and complacently morbid universe of certain individuals. On the contrary, the etchings display a sort of optimism and confidence in human nature. Walking Man, a recurrent figure in Maes’ work, is, above all, a man holding himself upright. Only a man, one might say, but a man moving forward. Alone and imperturbable, he imposes his presence. What David Maes draws our attention to is the dignity man acquires through the burden of his destiny. The walking man goes forward and nothing else matters.

The themes around which the etcher’s needle circles endlessly sometimes border on the mystical. The Voice, a dry point with a composition resembling that of a diptych, is an illustration of this tendency. In the lower left-hand area, a man advances, forehead thrust forward, slightly bent over. Only the upper half of the body is visible. To the right and above, is a suspended figure: a voice, a whisper, or an angel (as suggested by the title of the painting, Man and Angel, which was executed a few years earlier and which has a similar composition). This tutelary figure, who in the etching is not as explicitly named, bears witness to the fact that, despite his solitude, man has not been abandoned.

Other traditionally religious themes appear occasionally in David Maes’ etchings. In particular, he has long been interested in the crucifixion. In Three Studies of the Human Body of 1993, he approached that subject in a totally original manner, by relating it to a ritual which has long fascinated him: bullfighting. The title, deliberately neutral, does not at first suggest the world of the bull ring. Nevertheless, the pose of the figure in each of the three etchings has its parallel in the torero’s repertoire of stances. But into each print, in the midst of this play of comparisons, slips the figure of death. Carried in triumph on the shoulders of one of his companions, the torero is reduced to a skeleton; his body, its cape removed, is sundered, crucified. In the final image, poised to place his invisible darts, the body of the bandillero is arched, bow-like, from suffering. The overall composition recalls once more the world of bullfighting because the juxtaposition of the bodies in the three etchings echoes the semi-circle of the arena.

David Maes’ etchings, with their multiple layers of meaning, transform themselves beneath our gaze. In a recent work, Daphne (I), depicting a story from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, he has made this transformation visible. Before our eyes Daphne is changed into a laurel tree - and then, as we watch, the tree changes back into a woman. Because of its capacity to record successive ‘states’, the medium of etching is ideal for representing the stages of a metamorphosis. By contrast, unless the artifice of photography is exploited, the stages of a painting are condemned to disappear under each fresh stroke of the brush. It is not until the seventeenth state that the image of the woman becomes truly stable. From that point onwards, we can observe her evolution. She crouches and her outstretched arms blossom. Exhibiting each of the states makes it possible to demonstrate the metamorphosis in the same way a film can demonstrate the opening of a flower.

This particular transformation seems long. Time passes slowly. The metamorphosis becomes palpable, almost conscious. In another work, Daphne (II), David Maes cuts the process short. There, he merely juxtaposes two instants in a vertical diptych. The metamorphosis is reduced to a single shock. A body submits itself to gravity and falls. (For once, the body is not strictly human but takes on, perhaps under the weight of our gaze, something of the animal.) Above the falling figure, a vegetable form spreads out. The opposed movements of the body and the plant further reinforce the violence of the shock, the irreversible character of the change. The manner in which David Maes treats the theme of metamorphoses shows that far from wanting to enclose his work within the limits of a static universe, he is determined to explore the whole range of possibilities.

Marie-Hélène Gatto

Curator, Bibliothèque nationale de France

© David Maes - ADAGP Paris 2025