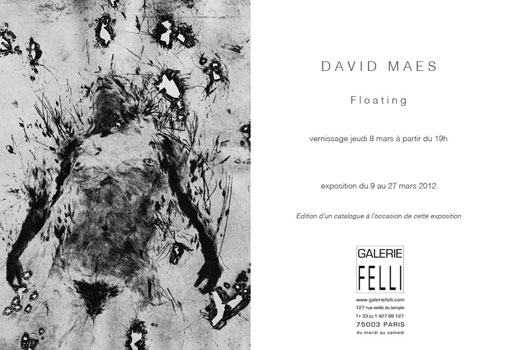

Floating Roots

"Floating", Galerie Felli, Paris, France, du 9 au 27 mars 2012

Qui, comme moi, marche aux côtés de David Maes depuis longtemps, connaît sa préoccupation de l’enracinement et, en concomitance, celle de l’errance. Dans sa vie et dans son travail. Ses personnages, hommes et femmes, marchent, errent, flottent, nagent, nus, obstinés ou à la dérive, des lambeaux de matières, des flammèches, des bris de lignes agrippés à leurs contours. L’exposition aurait pu s’appeler « Floating Roots ». David Maes a toujours eu l’obsession d’ancrer ses figures dans un réel qui, tout en capturant le temps, ne se réduise pas à un décor. Peut-être n’a-t-il trouvé au cours de ces décennies, dans une époque réticente jusque lors à la représentation de la figure humaine, d’autre moyens que de les faire renaître des éléments. Une manière aussi de louvoyer entre le réalisme et la suggestion, et d’éviter autant que possible les écueils du « beau nu » et de la nostalgie, en s’affranchissant toujours douloureusement de la question d’un temps et d’un lieu. La gravure, en offrant la plaque de cuivre ou de zinc aux morsures du stylet, en proposant une réalité inversée, lui permet sûrement de se libérer intellectuellement de la question et d’ouvrir la voie au jeu mystérieux des forces. Les représentations issues des voyages en Asie et en Afrique en témoignent davantage que les autres, peut-être parce qu’elles gardent le souvenir de la matière, de la terre rouge, de la boue, de l’eau, du dessèchement, de la brûlure du soleil, de la soif. A l’instar de Dieynaba qui, un jour, à la frontière de la Mauritanie, nous avait dit : « chez vous, il n’y a pas de poussière », car la poussière, pour elle, ce n’était pas la fine couche qui se disperse d’un coup de chiffon, mais une poussière drue et envahissante qu’il lui fallait chaque matin repousser en balayant le sol de terre battue de sa cour, dans ce corps à corps perpétuel avec la matière dont nous nous croyons libérés. Étrangement, ce sont les dessins et les gravures inspirés par ces voyages qui se rattachent d’eux mêmes à une certaine contemporanéité, comme cet homme qui étanche sa soif, canette à la main, dans un geste qui conduit tout naturellement à l’objet. Le b.a.-ba d’une histoire compréhensible pour chacun. D’autres histoires sont à venir. Car si marcher est le propre de l’homme debout, la marque d’un nomadisme qui couve malgré la sédentarisation ou qui nous menace toujours au gré des caprices des époques, l’homme peut aussi s’arrêter, gagner la rive, et, alors, avoir le temps de se représenter avec d’autres, avec les choses, avec les objets. Mais comment représenter cela ? Avec quels scénarios, autres que ceux que nous avons rejetés ? Comment faire une représentation du lien et du rapport qui ne soit pas un péril ou qui n’exclut pas celui qui regarde ? Je sais que c’est le risque que David Maes prend dans son expression, et qu’il continuera à prendre.

Sylvie Cavillier

Anyone who, like me, has walked beside David Maes for a long time, knows of his preoccupation with rootedness and, at the same time, with wandering. In his life and in his work. His personages, men and women, walk, wander, float, swim, naked, purposeful or adrift, with shreds of matter, sparks, fragments of line clinging to their contours. The exhibition could have been called “Floating Roots.” David Maes has always been obsessed with anchoring his figures in a reality which captures time and is more than mere decor. In a period that, until recently, has been so reticent about representing the human figure, he has not found any means of doing this other than having the people he depicts give birth to their own environment. This wavering between realism and suggestion has enabled him to avoid the pitfalls of the beau nu and of nostalgia, thus freeing him - always painfully - from the question of time and place. Printmaking, in submitting a copper or zinc plate to the bite of a stylus and presenting a reversed version of reality permits intellectual liberation from this question and opens the way to a mysterious play of forces. The images which have their source in trips to Asia and Africa bear witness to this more strongly than others, perhaps because they retain the memory of matter, the red earth, the mud, the water, the drought, the burning heat of the sun and of thirst. Following the example of Dieynaba who, one day, on the Mauritanian border, said to us, “Where you come from there is no dust,” because dust, for her, is not a thin layer of fine dust which can be wiped away with a light cloth, but a thick, invasive dust which, every morning, has to be swept off the beaten earth floor of her courtyard, in this perpetual hand-to-hand battle with the matter which we believe ourselves to be liberated from. Strangely, it is the drawings and prints which are inspired by these journeys which have a certain contemporary quality, such as that of the man, who, gripping a small tin, quenches his thirst with a gesture that leads quite naturally to the object. The a-b-c-d of a story anyone can understand. There will be more in the future. For if walking is the characteristic activity of upright man, the mark of a nomadism that still lies dormant within us despite the ever-present danger of being trapped in a completely sedentary life, we can still stop walking, reach the river bank and, then, take the time to interact with others, with things, with objects. But how is an artist to represent that? With what scenarios other than ones that have already been rejected? How is he to create a work of art that expresses this vision of humanity integrated with its surroundings without damaging it and without excluding his audience. I know these are the risks that David Maes faces in his work and that he will continue to face.

Translated by Forrest Lunn

© David Maes - ADAGP Paris 2025